The Psychological Impact of Demonizing Food Groups

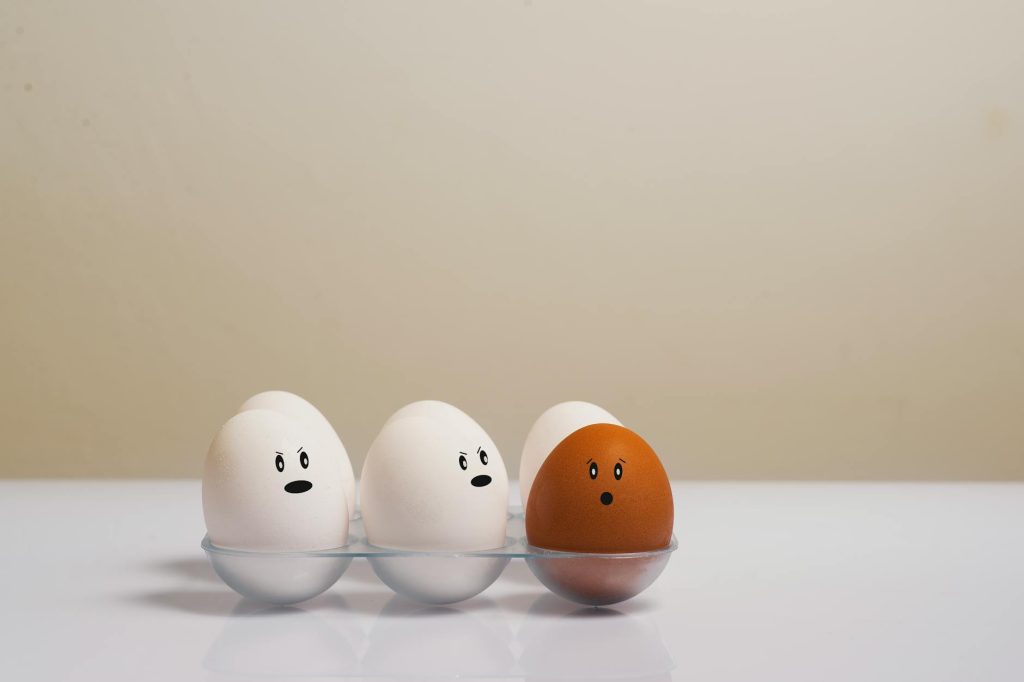

In today’s wellness-obsessed culture, we’re constantly bombarded with messages about what we should and shouldn’t eat. Foods are routinely labeled as “toxic,” “inflammatory,” “poison,” or “the enemy.” While certain dietary choices clearly impact health outcomes, the psychological consequences of demonizing entire food groups deserve much closer examination. This growing tendency to categorize foods in extreme terms may be causing more harm than the foods themselves.

The Psychology Behind Food Demonization

When we categorize foods as inherently “good” or “bad,” we create a moral framework around eating that can profoundly affect our relationship with food and ourselves. This black-and-white thinking removes the crucial nuance from our understanding of nutrition and triggers several psychological responses:

Guilt and Shame Cycles: The Forbidden Fruit Effect

Research in cognitive psychology demonstrates that labeling foods as “forbidden” paradoxically increases their desirability through what psychologists call “ironic process theory.” Studies by Dr. Janet Polivy at the University of Toronto show that restricted foods become more salient and attractive in our minds.

When we inevitably consume these “forbidden” foods—as most humans eventually do—intense feelings of guilt, shame, and perceived moral failure follow. Dr. Evelyn Tribole, co-creator of Intuitive Eating, explains that this negative emotional cascade can trigger either stress eating (seeking comfort) or further restriction (as penance), creating an unhealthy psychological cycle that damages both mental and physical health.

The neurochemical response is telling: consuming “forbidden” foods after restriction often results in increased dopamine release, reinforcing both the desirability of the food and the subsequent guilt, creating a difficult cycle to break.

Increased Anxiety Around Food Choices: The Paralysis of Perfection

When certain options are framed as dangerous, ordinary food decisions become sources of significant anxiety. A 2018 study in the Journal of Health Psychology found that exposure to fear-based nutritional messaging increased cortisol levels (a stress hormone) when subjects were later presented with food choices.

People report experiencing intense stress when dining in social settings, traveling, or when unable to control every ingredient in their meals. This hypervigilance around food can become all-consuming, with some individuals spending hours researching, planning, and worrying about food choices—mental energy that could be directed elsewhere in their lives.

Development of Disordered Eating Patterns: When “Healthy” Becomes Harmful

The line between “health-conscious eating” and disordered patterns can be remarkably thin. Longitudinal research published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders demonstrates that rigid food rules and fear-based messaging around food groups strongly correlate with increased risk of developing clinically significant eating disorders.

The transition from “clean eating” to orthorexia nervosa (an unhealthy obsession with eating foods deemed “pure” or “correct”) can be particularly insidious because it often begins with seemingly positive health intentions. Dr. Steven Bratman, who coined the term orthorexia, notes that what begins as an attempt to improve health can transform into a pathological fixation that actually damages health.

Nutritional Deficiencies: The Irony of Restriction

Paradoxically, eliminating entire food groups without proper planning can lead to nutritional gaps. When certain foods are vilified:

- Calcium and vitamin D deficiencies may arise from avoiding dairy without adequate replacements

- B-vitamin inadequacies can result from eliminating whole grain sources

- Essential fatty acid imbalances may occur when certain fats are deemed “bad”

These deficiencies can affect mood regulation, exacerbating anxiety and depression—creating a vicious cycle where poor nutrition impacts mental health, which further impacts eating behaviors.

Social and Cultural Consequences: Beyond the Individual

Food demonization extends beyond individual psychology to affect our social connections and cultural heritage:

Social Isolation and Relationship Strain

Research from Cornell University found that individuals following highly restrictive diets reported 33% more social discomfort and were more likely to avoid social gatherings where “forbidden” foods might be served. This self-imposed isolation reduces quality of life and access to social support networks crucial for mental health.

Family meals and relationships can become strained when food choices become moral battlegrounds. Partners and children of those with rigid food rules often report walking on eggshells around meal times, and the transmission of food fears to children is particularly concerning from a developmental perspective.

Cultural Disconnection and Loss of Food Heritage

Many traditional foods and cultural eating practices include items that may be demonized in certain diet cultures. For individuals from cultural backgrounds with strong food traditions, this can create painful cognitive dissonance and disconnect them from their heritage.

Anthropological studies show that traditional food cultures often have internal balancing mechanisms that naturally moderate consumption of various foods—mechanisms that are lost when foods are removed from their cultural context and labeled as simply “good” or “bad.”

Economic and Privilege Dimensions

Food demonization often ignores socioeconomic realities. When certain foods are vilified without acknowledging barriers to alternatives—such as cost, availability, time for preparation, and cultural accessibility—it creates additional layers of shame for those with fewer resources, effectively moralizing privilege.

The Neurobiological Impact: How Food Fear Affects the Brain

Emerging neuroscience research reveals how food fears impact our neurological functioning:

Stress Response Activation

When surrounded by messages that certain foods are dangerous, the amygdala (our brain’s threat detection center) becomes hyperactivated around food choices. This chronic low-grade stress response affects:

- Digestive function (reducing nutrient absorption)

- Metabolic processes (potentially increasing fat storage)

- Executive function (impairing decision-making capabilities)

Disruption of Interoceptive Awareness

Interoceptive awareness—our ability to perceive and interpret internal bodily signals like hunger and fullness—becomes compromised when external rules override internal cues. Neuroimaging studies show altered activity in the insula (the brain region responsible for interoception) among individuals with rigid eating rules compared to those with more flexible approaches.

A More Balanced Approach: Psychological Nutrition

A healthier relationship with food integrates physical and psychological nutrition through several evidence-based principles:

Flexible Restraint vs. Rigid Control

Research by Dr. Jillon Vander Wal distinguishes between two approaches to nutrition:

- Rigid control: All-or-nothing rules, moralized foods, perfectionistic standards

- Flexible restraint: General nutritional awareness with adaptability, contextual choices, and absence of moral judgment

Studies consistently show that flexible restraint correlates with better long-term health outcomes, sustainable behavioral changes, and significantly lower rates of disordered eating than rigid control—while achieving similar or better physical health metrics.

Food Neutrality and the Value of Variety

Adopting food neutrality—the understanding that foods have different nutritional profiles but no inherent moral value—allows for more balanced decision-making. Dr. Christy Harrison advocates for recognizing that:

- Foods exist on a nutritional spectrum, not in absolute categories

- Different foods serve different purposes (nutrition, pleasure, cultural connection, convenience)

- Variety and moderation naturally lead to nutritional adequacy for most people

Mindful Eating Practices

Mindfulness-based approaches to eating focus on:

- Attentive consumption without judgment

- Reconnection with physical hunger and fullness cues

- Appreciation of sensory aspects of eating

- Consideration of how different foods affect individual well-being

Research from Indiana State University found that mindful eating interventions produced greater improvements in both psychological measures and physiological markers than restrictive dieting approaches.

Practical Applications: Moving Beyond Food Fear

Individuals seeking a healthier relationship with food might consider:

- Working with nutrition professionals who emphasize a non-diet approach

- Practicing gentle nutrition that considers both physical and mental health

- Examining the evidence behind nutritional claims before eliminating food groups

- Considering the personal, cultural, and social context of eating decisions

- Understanding that psychological well-being is a crucial component of overall health

Healthcare providers and nutrition educators can help by:

- Avoiding fear-based messaging around food

- Providing context-sensitive nutritional guidance

- Screening for disordered eating patterns before recommending restrictions

- Acknowledging the potential psychological impact of dietary recommendations

- Focusing on addition rather than elimination when possible

Conclusion: Toward Food Peace

While it’s reasonable and beneficial to make informed choices about nutrition, creating fear and moral judgment around food groups often creates more harm than benefit. The research increasingly points toward a gentler, more inclusive approach to nutrition that honors both physical and mental health outcomes.

By understanding the psychological impact of food demonization, we can work toward a more balanced relationship with eating—one that nourishes both body and mind, allows for pleasure and connection, and recognizes that true wellness encompasses far more than simply avoiding certain foods.